Canterbury has gone through quite a change throughout its history. Beginning as a Catholic Cathedral full of finery and luxury, it went through a drastic change during the Reformation. As the Anglican Church and the Church of England took over as the dominant form of Christianity. Lutheran values saw drastic changes to the church as the new tradition took a stance:

‘to reject the great display of bulls, seals, flags, indulgences’ (n.d [1520] p.18).

In this piece we will look at how this change in tradition lead to changes in Canterbury and how this was a signifier of the social and religious changes which occurred during the reappraisal of Christianity in the west.

Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury was struck down by Henry II’s knights in a misunderstanding. They mistook Henry’s wish for Becket, or as Henry II describes him ‘Meddlesome priest,’ to be dealt with seriously. After his murder and assent to sainthood, Becket was taken and placed in the crypt between 1170 and 1220. During this time, people would enact many a pilgrimage to see the resting place of the Saint.

They would leave votive offerings of candles in body part shapes and crutches as signs of cure. The tomb in the middle of the room held his body and had holes. Those who had come to ask the saint for guidance or aid would place their faces in and kiss the tomb. These holes were also small enough to ensure that no part of the relic could be stolen. During the reformation, the now unused shrine was emptied out with the change in religious regime. Votive offerings were destroyed. In the view of reformists, people should not be in acting on pilgrimages to visit such a place of indulgence. They should not be buying their way to salvation. Instead, they should be praying to God, devoting themselves to him, not attempting to appease a saint. The Crypt was not the biggest causality of the Reformation, however, that would be the Trinity Chapel.

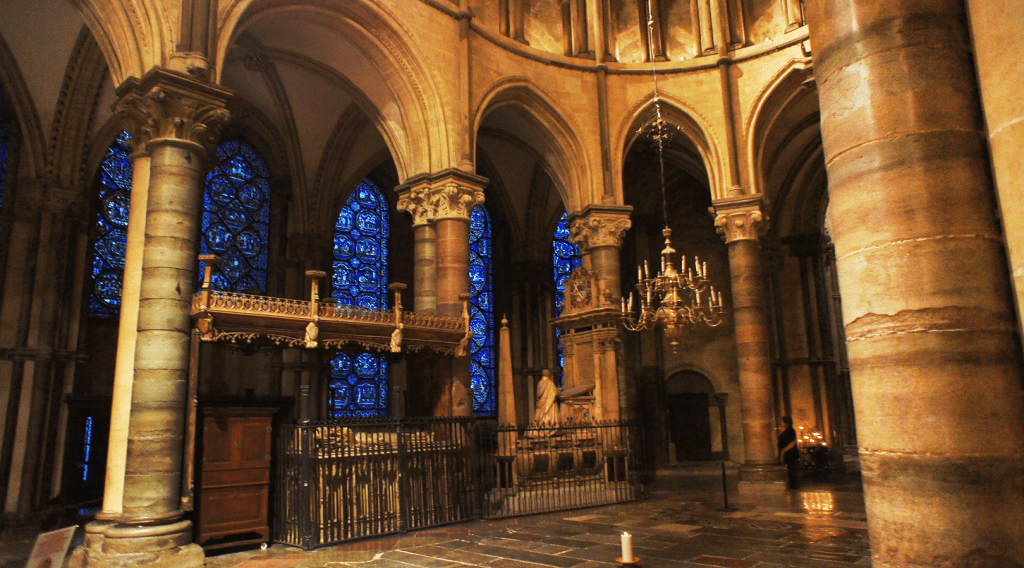

The Trinity Chapel played host to a grand and lavish new resting place for Saint Thomas from 1220 until the beginning of the Reformation. Gates sat in front of the golden casket which could be lifted and lowered onto a marble pedestal. These gates allowed for control of access. A monk would oversee those wishing to pray to the Saint asking for guidance, healing or help in their lives. Much like in the crypt, votive offerings would be left. Within the Chapel also stood Miracle Window. An area in which votive offerings were shown and ‘miracles’ were documented, all in the name of Saint Thomas. The whole chapel was a lavish and indulgent affair, which lead to the Reformists and those who agreed with Lutheran doctrine to destroy the once beautiful site in 1538. The golden tomb destroyed which in turn ceased pilgrimage to the site. As many Reformists saw these Pilgrimages as merely a distraction to finding salvation in God. Today, the effects of the Reformation are still visible.

Becket’s tomb long gone, nothing more than a memory, with a solitary candle marking where it once stood. There are no more pilgrims arriving to marvel at the golden tomb of the saint. Almost all material expressions related to Becket went down with the tomb during its destruction. Miracle Window however still stands, offering a window into the past, showing what little material culture survived the reformation purge. It is not as popular as it once was, due to the change in religious practices in England. Brought on by fear of being a social outcast for following a practice long disowned by English Religious establishment. All that said, the Trinity Chapel, once teeming with pre-reformation luxury, now very much conforms to the Lutheran doctrine. Rejecting the ‘great display of indulgence’ (n.d. [1520], p. 19).

Finally, we move to the Corona Chapel, which during the time before reformation housed a fragment of Saint Thomas’ skull. The piece of skull had been split from the rest during his murder. It was in the Corona Chapel, monks, clerical visitors, and those of high status, royalty and the rich, would view his skull fragment and pray to Saint Thomas. The piece of skull was placed onto a ‘reliquary’ that was, much like his tomb, adorned with gold and jewels. During the Reformation, any relic the Reformists could get their hands on were destroyed. However this fragment of Saint Thomas surprisingly escaped such a fate. Sources such as the Anglican Communion News Service and the British Broadcasting company reported in 2016 that the relic was returned to the UK from Hungary. It was now touring the south of the UK. Visiting many churches in what the article from the Anglican News dubbed ‘Becket Week.’ (Anglican News 23 May 2016 Becket’s bones return to Canterbury Cathedral). Whilst its material relic survived, the Corona Chapel now stands as a testament to times gone by. Renamed as The Chapel of Saints and Martyrs of our Time, it is not the golden meeting place for those at the top the religious hierarchy. It holds no material culture, save for a few stained-glass windows. Much like the Crypt and Trinity Chapel, a shadow of its pre-reformation state. As the ideas of lavish tombs, pilgrimages, and votive offerings became barren and plain places to allow for salvation without distraction.

Canterbury was a heavy causality in the reformation. With Henry VIII going to great lengths to rid the church of any indulgence and corruption he saw. We can see this in the destruction of its material culture. The lose of the tomb, the once marvelous and expensive designs replaced with more dull and completive places. To worship the lord in without distraction. Anything seen as unnecessary, or ill-fitting of the new Anglican religion was destroyed. Now we have very few ways to look back on that time. The skull fragments which escaped destruction. The miracle window. Very few surviving pieces of a time in which social and religious attitudes were vastly different from the way they are today. We can view Luther’s ideas now as commonplace; however, the social changes cannot go unnoticed. Once vibrant rooms of prayer and pilgrimage now lay bare, a single candle commemorating what once was. Those who did not wish to follow this new religion outcast, all because of a man who wished for a different way. Canterbury will always be a marvel, its architectural beauty forever being known, however it will always be missing its material culture, its history. For better or worse, a piece of it will always be lost in time.

Bibliography

- Morgan, D. (2008) ‘The materiality of cultural construction’, Material Religion, 4(2), pp. 228–9.

- Bowman, M. (2019) ‘Christianity and its material culture’, in Hughes, J. (ed.) Traditions. Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 301–36

- The Architectural History of Canter…, Woodman, Franci

- (2016 May 23) ‘Becket’s Bones return to Canterbury Cathedral’ Anglican Communion News Service. Available at: https://www.anglicannews.org/news/2016/05/beckets-bones-return-to-canterbury-cathedral.aspx

- The Early History of the Church of …, Brooks, Nicholas